A common misconception in genealogy is the idea that African Americans cannot trace their ancestry beyond the 1870 Federal Population Census. This myth, often referred to as the “1870 Brick Wall,” suggests that records of African American ancestors, particularly those who were enslaved, are virtually non-existent before this pivotal year. However, this is far from the truth, so please stop referencing this. You all know who you are. No one can guarantee you will find your ancestors, but this information will help you tremendously. Do not give up and stay focused. Numerous records and resources exist that can help trace African American lineage back to the early 19th century and even further.

First let me cover a little background on the 1870 Census

The 1870 Federal Population Census holds a pivotal place in African American genealogical research. Conducted just five years after the end of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, it was the first U.S. census to enumerate all African Americans, both free and formerly enslaved. This provides an invaluable view of African American life during a transformative period in American history. However, while the 1870 Census is still a crucial resource, but it also comes with certain challenges that researchers must navigate.

Here are four points of importance of the 1870 Census for this blogs focus:

1. First Comprehensive Enumeration: The 1870 Census is the first to list African Americans by name, including those who were formerly enslaved. This marked a significant departure from previous censuses, where enslaved individuals were enumerated without names, often only noted by age and gender under the slaveholder’s household (example: 1850 & 1860 Slave Schedules)

2. Post-Civil War Transition: This census captures African American families in the immediate aftermath of emancipation, providing insights into their new-found freedom, occupations, and living arrangements. It reflects the social and economic adjustments made by formerly enslaved people as they transitioned to freedom.

3. Family Reconstitution: For genealogists, the 1870 Census is a critical starting point for reconstructing African American family histories. It often provides the first official record of family units and can be used to connect individuals to earlier records, such as those from the Freedmen’s Bureau, Freedman’s Bank, or plantation records.

4. Geographical Mobility: The census helps trace the movements of African American families during the Reconstruction era. Researchers can track relocations, which were often driven by the search for economic opportunities, family reunification, or escaping the oppressive conditions of the South.

There are known challenges of the 1870 Census (or any census):

1. Name Changes and Variations: Following emancipation, many African Americans adopted new surnames or altered the spelling of existing ones. This can create challenges in linking individuals in the 1870 Census to earlier records. Variations in spelling and recording errors by census enumerators can further complicate our research process.

2. Incomplete or Inaccurate Information: The 1870 Census, like all historical records, has inaccuracies. Enumerators might have recorded information incorrectly due to language barriers, misunderstandings, or bias. Some individuals might have been omitted or double-counted.

3. Limited Data on Enslaved Ancestors: While the 1870 Census provides names and details for formerly enslaved individuals, it does not offer direct links to their life during slavery. Researchers often need to use supplementary records such as plantation records, wills, and Freedmen’s Bureau documents to bridge this gap.

4. Fragmented/broken Families: The disruption caused by slavery, the Civil War, and the immediate aftermath often led to fragmented families. The 1870 Census might show individuals living apart from their immediate family members, making it challenging to piece together family units and histories accurately.

5. Lack of Previous Census Records: Prior to 1870, enslaved individuals were not listed by name in federal censuses, appearing only in slave schedules under the names of slaveholders. This absence of named records requires researchers to rely heavily on other documents, such as estate records, manumission papers, and church records, to trace lineage.

A little help getting through the challenges:

Despite these challenges, the 1870 Census remains a cornerstone for African American genealogical research. Here are few strategies I recommend to overcome these obstacles:

– Cross-Referencing Records: Use multiple sources to verify and supplement the information found in the 1870 Census. Freedmen’s Bureau records, Freedman’s Bank records, military records, and church records can provide additional context and details.

– Local Histories and Oral Traditions: Community histories and oral traditions can offer clues and corroborate census data. They can help fill in gaps and provide narratives that official records may not capture.

– Collaborative Research: Engaging with genealogical societies, online forums, and local historical societies can provide support and resources. Collaborative research can uncover connections and insights that might be missed when working alone.

– DNA Testing: Genetic genealogy can be a powerful tool to connect with distant relatives and corroborate historical records. DNA testing can help break through the 1870 “brick wall” by identifying shared ancestors and linking family lines.

The 1870 Federal Population Census is a foundational resource for African American genealogical research, marking the first official record of African Americans as free individuals. While it presents unique challenges, the wealth of information it provides is indispensable. By understanding its limitations and employing a comprehensive approach to research, genealogists can unlock the rich and complex histories of African American ancestors, reaching back through time to illuminate their enduring legacy.

Here are specific records and resources to research to assist with locating African Americans prior to the 1870 Federal population census.

- Freedmen’s Bureau Records (RG 105, 3.5 million)

Location: National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)

The Freedmen’s Bureau, officially known as the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, was established in 1865 to aid formerly enslaved individuals during the Reconstruction era. Its records include marriage records, labor contracts, educational records, and more. These documents can provide critical information about African American families immediately following the Civil War. This is my favorite collection!

- Freedman’s Bank Records (RG 101)

Location: National Archives, FamilySearch, Ancestry

The Freedman’s Bank, established in 1865 to help formerly enslaved individuals manage their finances, created detailed records for each account holder. These records often include names, places of birth, family members, and sometimes even physical descriptions, offering a wealth of genealogical information.

- 3/5 Compromise Records

Location: Various archives and historical repositories

The 3/5 Compromise led to detailed records in tax documents, census records, and other governmental documents where enslaved individuals were counted as three-fifths of a person. These records, often overlooked, can provide data about enslaved populations in different states.

- Slave Narratives

Location: Library of Congress, Various state archives

The Federal Writers’ Project of the 1930s collected firsthand accounts of formerly enslaved individuals. These narratives provide personal details and historical context that can be invaluable for genealogical research.

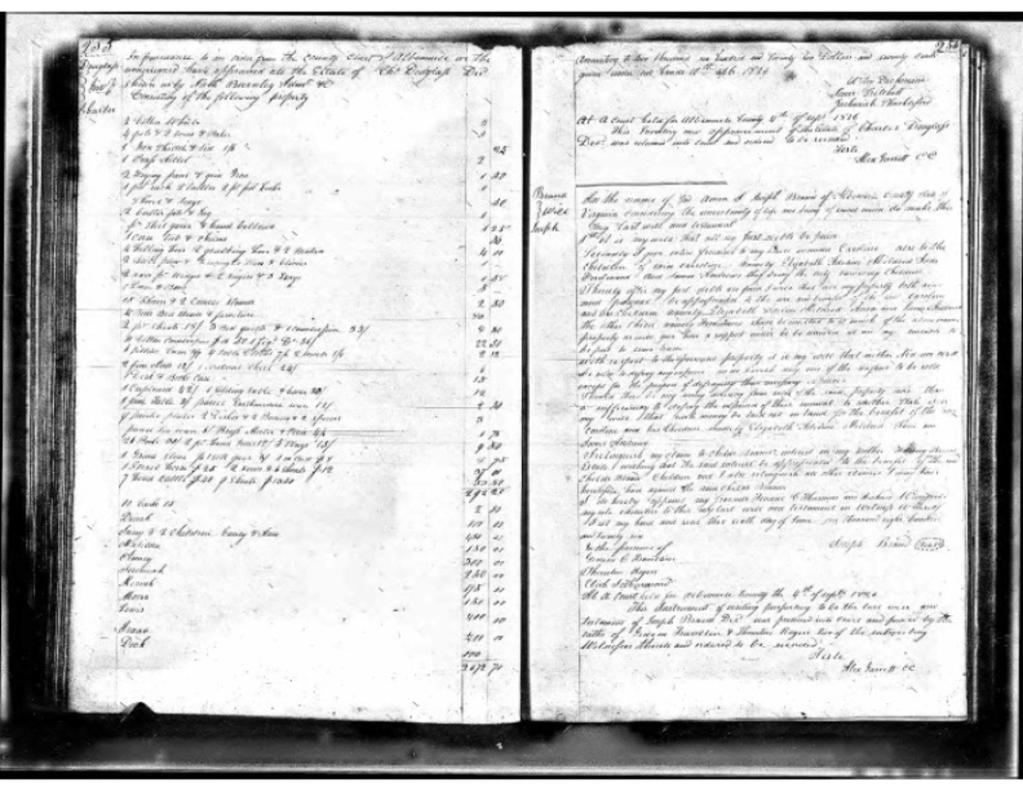

- Estate Records and Wills

Location: Local courthouses, state archives

Estate records and wills often listed enslaved individuals by name as property of the deceased. These records can provide names, relationships, and even ages, helping to piece together family connections.

- Plantation Records

Location: University archives, state historical societies

Plantation records, including ledgers, work logs, and personal correspondence, can provide detailed information about the lives of enslaved individuals. Many universities and historical societies hold these collections, which are often digitized for easier access.

- Manumission Records

Location: Local courthouses, state archives

Records of manumission (the formal emancipation of enslaved individuals) can provide valuable information. These documents often include names, ages, and descriptions of the individuals freed, along with details about their former enslavers.

- Free Black Registers and Notarial Records, etc.

Location: Local courthouses, state archives

Before the Civil War, some states required free African Americans to register with local authorities. These registers can include names, ages, places of residence, and even occupations.

- Military Records

Location: National Archives, Fold3, Ancestry

African Americans served in various military capacities before and during the Civil War. Military records, including service records and pension files, can offer personal details and family connections.

- Church Records

Location: Local churches, denominational archives

Churches often kept detailed records of their members, including births, baptisms, marriages, and deaths. These records can be a treasure trove of information, especially in communities where official civil records were not kept.

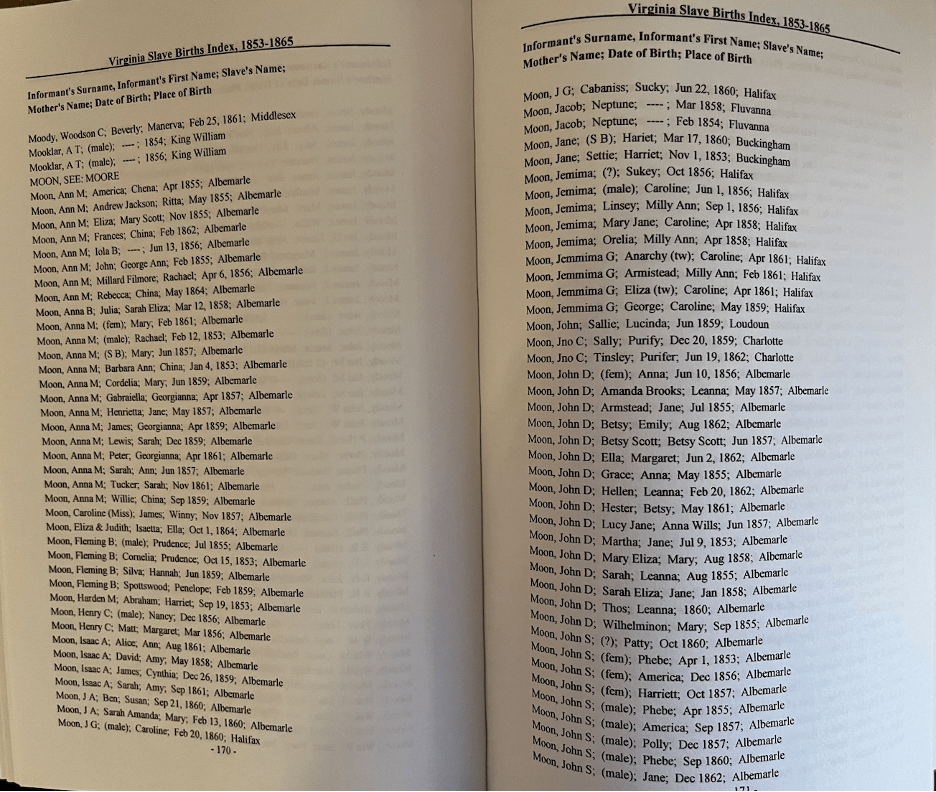

- Virginia Slave Birth Index (1853-1865)

- Location: Virginia state archives

- Details: Birth records of enslaved individuals, providing names and details of enslaved mothers.

The myth that African American genealogical research hits an insurmountable barrier at 1870 is not only misleading but also discouraging to those seeking to uncover their family history. By exploring the diverse array of records available before 1870, you can piece together the stories of their ancestors, both free and enslaved. It’s essential to approach this research with an open mind and a willingness to delve into various types of records. With perseverance and the right resources, the rich and complex history of African American families can be brought to light, dispelling the 1870 myth once and for all.

Happy researching!

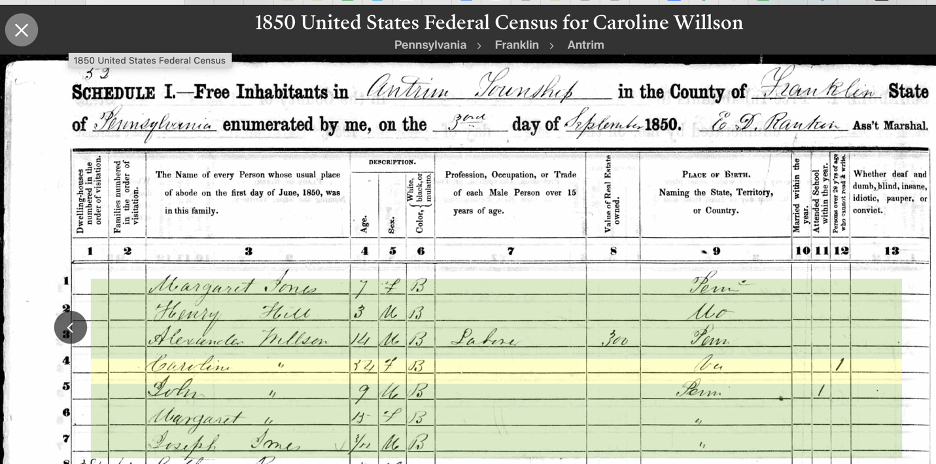

1870 Census Franklin County, PA-Caroline (Line 4, was freed in 1826 by her slave owner and father of her children:

David Brown -labor contract VA Freedmen’s Bureau on familysearch.org

Will of Joseph Brand Jr, 1826, Albemarle County, VA list of enslaved and giving them Freedom

Virginia Slave Birth Index 1853-1865-Moon Family, Albemarle Co. VA

Leave a reply to Eilene Lyon Cancel reply